Fustanella – The Skirt of Greek Soldiers: 400 Folds of History, Pride, and Heroism

Can a men’s skirt be a symbol of bravery and national pride? In Greece - absolutely. The fustanella (Greek: φουστανέλα) is a traditional garment resembling a pleated skirt worn by men. Made from dozens- sometimes hundreds-of narrow folds, it forms a white, flared kilt reaching roughly to the knees. This striking outfit has its roots in the mountainous regions of the Balkans and has evolved into one of the most recognizable Greek national symbols. Once proudly worn by mountain warriors, it is now admired by millions of tourists on the streets of Athens.

This article explores the long and fascinating history of the fustanella - from ancient inspirations and the Greek War of Independence to its modern ceremonial role - and the cultural meaning hidden in every fold.

What Is the Fustanella?

The fustanella is a traditional men’s garment that closely resembles a pleated kilt. Usually made of white cotton fabric, it is distinguished by its large number of narrow folds. Although visually reminiscent of the Scottish kilt, the fustanella developed independently in the cultural environment of southern Europe.

Historically, the fustanella was worn in Greece, Albania, and other Balkan regions as both a folk costume and a type of military dress. In Greece, it became especially popular in the mountains. Over time, the white, flared skirt with hundreds of folds grew into an iconic part of Greek national dress, so much so that today it’s nearly impossible to imagine the ceremonial guards in Athens- the Evzones- without their fustanellas.

Despite its skirt-like appearance, the fustanella served the same social function as many other traditional male garments: it symbolized masculinity, courage, and social status. Wearing it required strength-simply because of its weight and volume—and arranging its folds properly was a demanding art. Historically, the garment was favored by highland warriors and members of armed bands rather than by everyday farmers. Before the creation of the modern Greek state, the fustanella was the attire of klefts (mountain bandits and resistance fighters) and armatoloi (local militia). Only later did it become a national symbol embraced by the entire country.

Ancient Roots of an Extraordinary Garment

The origins of the fustanella are as layered as the garment itself. Several theories trace its beginnings to ancient Greek and Roman clothing. Some scholars see a connection to the ancient Greek chiton—a short tunic sometimes belted in a way that created folds resembling those of the fustanella. Others point to Roman military uniforms: Roman emperors and soldiers are often depicted wearing armor with short, pleated skirts that strongly resemble the later Balkan garment. These Roman-style tunics, worn throughout the Mediterranean, may have inspired regional clothing traditions after centuries of contact.

Archaeological findings support the garment’s long history. In modern-day Albania, figurines from the 4th century CE have been discovered showing men dressed in skirt-like attire similar to the fustanella.

The name “fustanella” likely derives from the Italian word fustagno (English: fustian), referring to a type of sturdy cotton fabric. The diminutive -ella suggests “a little skirt made of fustian”- which is exactly what early versions of the fustanella were. The etymology reflects the garment’s practical origins among mountain communities who needed durable material in a rugged climate.

From Outlaws to National Heroes

For centuries, the fustanella symbolized independence and the fierce spirit of Balkan mountain culture. In the 18th and early 19th centuries, it was commonly worn by klefts, the mountain bandits who simultaneously served as resistance fighters against the Ottoman Empire. It was also worn by armatoloi, militias appointed to maintain order in remote areas. Clad in white pleated skirts, these fighters inspired both fear and admiration.

When the Greek War of Independence erupted in 1821, many klefts and armatoloi became the core of the revolutionary army. Their fustanella-clad silhouettes transformed from those of outlaws to those of national heroes fighting for freedom. Legendary figures such as Theodoros Kolokotronis and Markos Botsaris became emblematic of the struggle, and their attire gained immense symbolic power.

European Philhellenes (supporters of the Greek cause) romanticized the image of the Greek freedom fighter. The British poet Lord Byron, among the most famous Philhellenes, was captivated by the traditional Albanian-Greek costume. He even wore it himself, describing it as “the most magnificent in the world,” featuring a long white skirt, gold-embroidered jacket, scarlet velvet coat, and ornate weapons. Byron’s admiration helped popularize the fustanella across Europe as a symbol of heroic resistance.

By the 1820s, the fustanella was featured widely in paintings, engravings, and literature celebrating the Greek revolution. It had become a symbol of bravery, sacrifice, and national identity, known far beyond the borders of Greece.

The Fustanella as Greece’s National Costume

After Greece won its independence, the new state embraced the fustanella as a key marker of national identity. In 1833, King Otto, the first monarch of modern Greece, issued a decree incorporating the fustanella into the uniform of the national army. Many soldiers were former revolutionaries, and the garment became a natural continuation of their wartime attire.

By 1835 the fustanella had been established as official court dress, and soon it came to represent the nation itself. Otto even posed for portraits wearing the fustanella of an Evzone (a Greek ceremonial guard), standing against ancient ruins to symbolize continuity between ancient and modern Greece. His wife, Queen Amalia, further promoted Greek dress by designing a national costume for women as well.

While Western European clothing eventually replaced traditional garments in everyday life, the fustanella survived as ceremonial dress. It remained prominent among certain military units, especially the Royal Guard, and in rural festivities and folk celebrations well into the early 20th century. Today, it lives on primarily through the Evzones, who preserve the tradition in its most iconic form.

Symbolism and Cultural Meaning

The fustanella is far more than a piece of clothing- it is a visual representation of Greek history and identity. Its elements carry layers of symbolism.

-

400 Pleats: The fustanella traditionally has 400 folds, each said to represent one year of Ottoman occupation. Although actual numbers may vary due to the complexity of tailoring, the symbolism remains powerful.

-

White Color: Represents purity, virtue, and freedom.

-

Red Fez (Farion): The red cap symbolizes blood shed for independence. The long black tassel represents the mourning of the nation for its fallen heroes.

-

Blue-and-White Tassels (Krossia): These decorative cords represent the colors of the Greek flag—symbolizing unity, sea, sky, and national identity.

-

Gold-Embroidered Vest (Fermeli): Often decorated with crosses or religious motifs, highlighting the role of Orthodoxy in Greek identity.

Together, these elements create a “wearable monument,” a garment that tells the story of Greece’s struggles and triumphs.

The Fustanella Today: Evzones as Guardians of Tradition

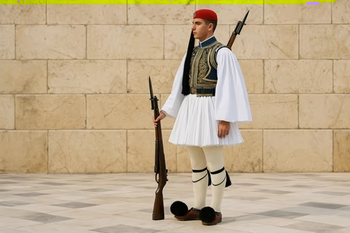

Today, the most famous wearers of the fustanella are the Evzones, elite ceremonial guards of the Hellenic Presidential Guard. They stand vigil at the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier in front of the Greek Parliament on Syntagma Square in Athens. Their duties include representing Greece at major national events and honoring fallen soldiers.

The Evzones are a living link between ancient tradition and modern Greek identity. Their precision, discipline, and striking attire make them one of the most photographed and admired symbols of Greece.

The Changing of the Guard

The ceremony occurs every hour, day and night, attracting crowds of visitors year-round. The most impressive event is the Grand Change on Sundays at 11:00 a.m., when the entire unit marches accompanied by a military band. During the week, two guards stand motionless until replaced by fellow Evzones in a synchronized, slow-motion march characterized by high leg lifts. Tradition says that these movements help restore circulation after standing still for long periods.

Becoming an Evzone requires exceptional height (about 1.87 m / 6′2″ minimum), physical endurance, and strict discipline. Soldiers undergo specialized training, including how to stand perfectly still and how to maintain the ceremonial uniform. Dressing in full regalia can take up to half an hour.

Although the Evzones wear alternate uniforms in winter or on special occasions, the fustanella remains the most iconic version, instantly recognizable to anyone visiting Athens.

place-post-preview-1-here:https://keepitgreece.com/en/article/why-the-changing-of-the-guard-in-athens-is-one-of-the-citys-top-attractions/

Fun Facts About the Fustanella and the Evzones

A Record Number of Folds

A traditional ceremonial fustanella is made from roughly 30 meters (100 ft) of fabric and features around 400 pleats. Maintaining these sharp folds requires steam irons and meticulous care.

Colors of Blood and Tears

The red fez symbolizes the blood of fallen heroes, while the black tassel represents the tears of the Greek people. The uniform itself tells the story of Greece’s path to independence.

National Colors in Every Detail

The blue-and-white tassels worn on the belt reflect the colors of the Greek flag, symbolizing unity and pride.

Heavy Boots with a Secret

Evzones wear tsarouchia, heavy leather shoes weighing about 1.5 kg (3.3 lbs) each, fitted with about 60 metal nails in the sole to make the signature sound on marble. The famous black pompons originally concealed blades—just in case a warrior needed a hidden weapon.

Master Tailors at Work

Each Evzone uniform has around a dozen components, many hand-sewn. The embroidered vest alone can take six months to make, and the knowledge behind the designs is passed down through generations of specialized artisans.

Not Only Greek

Although today strongly associated with Greece, the fustanella was once common throughout the Balkans, especially among Albanian highlanders. Both Greek and Albanian communities considered it a national symbol in the 19th century, a testament to shared cultural traditions.

A Living Monument of Greek Culture

The fustanella has survived centuries of social, political, and cultural changes. To a visitor in modern Athens, it may seem surprising that soldiers wear white pleated skirts in the heart of a cosmopolitan capital. But once you learn the story behind the garment, its presence becomes deeply meaningful.

Standing on Syntagma Square and watching the Evzones march, one witnesses not just a military ritual but a living expression of Greek heritage. Every pleat, every step, every detail carries hundreds of years of history. The fustanella is more than clothing- it is a symbol of the Greek spirit, proudly unfolding with every movement of the guards who protect it.